Magazine

The Labor of Freedom: Work and Life in Seneca Village

The next time you visit Central Park, take a walk to the top of Summit Rock—the Park’s highest point of natural elevation—where you can look out across the landscape that was once Seneca Village. Pause for a moment to reflect on what it may have been like to live in the Village as a Black New Yorker in 1855—going to work, cooking meals, attending school, raising a family. Who would your neighbors have been? What might your house have looked like? How would you have spent your days? Many Black Seneca Villagers were able to own their own homes and earn wages—but what did that freedom really look like?

A view of the Seneca Village landscape from Summit Rock.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History’s (ASALH) 2025 Black History Month theme is “African Americans and Labor,” focusing on “the various and profound ways that work and working of all kinds—free and unfree, skilled and unskilled, vocational and voluntary—intersect with the collective experiences of Black people.”

One of the many ways we can explore this theme is by looking back to Seneca Village, a community of free, predominantly Black landowners and families. Located along what is now Central Park’s perimeter from West 82nd to 89th Streets, Seneca Village existed from 1825 until 1857, when the City of New York used eminent domain to force the sale of the land to build Central Park. Residents were made to leave, rendering all traces of the settlement lost to history for the next century and a half.

In recent years, the Central Park Conservancy has undertaken a major effort to conduct new research and interpret Seneca Village, working to uncover the stories and lives of its residents. While there’s still much to learn, research has shed light on how its residents lived—where they worked, how they built their community, and what freedom looked like in practice for this group of Black New Yorkers in the 19th century. In these details, we find not just a history of labor, but a deeper story of resilience, autonomy, and the struggle for self-determination.

The Freedom of Community

Seneca Village provided a haven and respite for its Black residents. Although New York State’s gradual emancipation of enslaved people had been underway since 1799, slavery was not abolished until 1827, just two years after the establishment of Seneca Village. Even after Emancipation, Black New Yorkers still faced grave obstacles to freedom and citizenship, ranging from violent attacks to systemic discrimination in employment, housing, education, and more. Downtown, Black residents navigated a city rife with hostility, their movements restricted, their opportunities few.

But in this sparsely settled region of Manhattan, Seneca Village provided a refuge from the rampant racism and violence downtown, offering the chance to own land and build homes. In 1855, more than half of the Black households in Seneca Village owned their land, which was five times greater than the rate of property ownership among all New Yorkers. With this opportunity came a path to suffrage (though only for male property owners), stability, and a measure of autonomy that was otherwise elusive.

A map of Seneca Village from 1856, showing just a few of the properties owned by Black residents.

The Limited Freedom of Employment

With emancipation coming two years after Seneca Village’s founding, Black New Yorkers navigated the promise of wage-based labor and skilled jobs. Despite this progress, persistent racism meant that employment for Black people remained confined to a narrow set of roles. Most men living in Seneca Village were employed as laborers or service workers, their options dictated not by skill or ambition, but an unyielding racial hierarchy. Employment for male residents included:

- Employees of the churches in their own community:

- William Godfrey Wilson was the porter and sexton of All Angels’ Episcopal Church, the racially integrated “mission” church of the wealthy, white St. Michael’s church in Bloomingdale;

- William M. Mathew was a whitewasher and a preacher for African Union Church, the first church built in Seneca Village and one of two Black Methodist churches; and

- Ishmael Allen was a church sexton and possibly a blacksmith.

- Sailors: John White and James Davis, who may have brought back stories of far-off places.

- Cooks: Obidiah McCollin from Westchester, New York and Charles Sylvan from Haiti.

- Gardeners: Henry Garnet from Maryland, and Georgia-born Josiah Landin had a business planting ornamental shrubs.

An 1855 census listing Seneca Village residents. The highlighted excerpt includes: Andrew Williams, cartman; Elizabeth Williams; Jereimiah Williams, waiter; Ann E Williams; Elias Williams, 9 years old; John F. Butler, laborer; and Ellen A. Butler. (Ancestry.com)

In census records documenting the jobs of Seneca Villagers, very few women are listed as having occupations. This suggests that their primary work was taking care of their homes and families, and perhaps tending to an adjacent garden—highlighting the fact that job options available to free Black women in the 19th century were far more limited:

- Washerwoman: Sally Wilson from Virginia washed clothes for a living.

- Servants: At least several young Black women worked as domestics, or servants in wealthier households, hotels, or boarding houses.

- Teacher: Caroline W. Simpson taught at Colored School #3, the public school attached to the Village’s African Union Church.

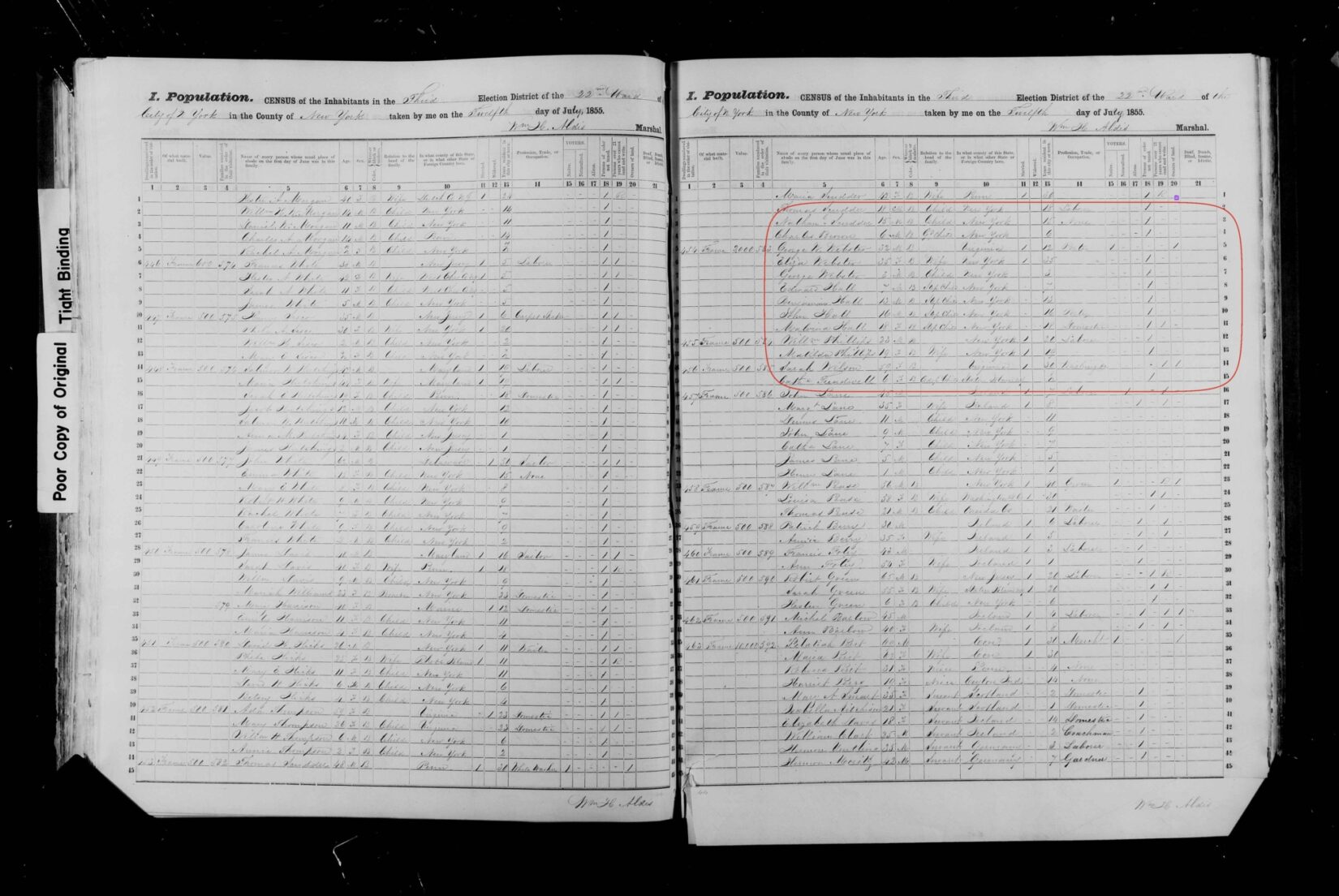

An 1855 census listing Seneca Village residents. The highlighted excerpt includes: George W. Webster (32), porter; Eliza Webster (35); child; child; child; John Hall (16), porter; Malvina Hall (18), domestic; William Phillips (23), laborer; Matilda Phillips (19); and Sarah Wilson (59), washing. (Ancestry.com)

Self-Sufficiency Through Domestic Labor

In Seneca Village, many Black residents enjoyed significant freedom through their daily, often invisible labor—the things we don’t see in census records. Historical maps and archaeological excavations have revealed a world of self-sufficiency.

Away from the crowded confines of lower Manhattan, Seneca Villagers had the space to plant vegetable gardens and raise animals for food, allowing them to be more self-sufficient and Iess dependent upon city markets or wages to meet their needs. From historical maps, we can see many Villagers had barns for livestock. An archaeological excavation of the Wilson family home in Seneca Village also unearthed many possessions belonging to William and Charlotte Wilson and their nine children. Among the artifacts found were locally made stoneware jars for preserving and storing food, and a lead fishing weight, which was likely put to use in the nearby Hudson River. These types of discoveries show us how much Villagers could provide for themselves right where they were.

Stoneware jar excavated from the Wilson family home. (Photo: The New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center)

Lead fishing weight excavated from the Wilson family home. (Photo: The New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center)

It’s also important to recognize who performed this work. While census records list no occupations for most of the women who lived in Seneca Village, it was common for women during that time to perform much of the domestic labor that benefited these families’ lives so significantly. We can infer that the women of the Village handled most of this vital labor while the men were otherwise occupied outside of the home. Like so much of history, Black women’s contributions to Seneca Village have been undocumented, forgotten, or erased—but the effects of their labor were lasting and profound.

The Freedoms Lost for Central Park

When residents of Seneca Village were forced to leave their homes in 1857, many moved to more densely populated areas, leaving behind a relatively remote community that provided them with a degree of agricultural and domestic autonomy. The network of self-sufficiency they had built—the gardens, the fishing spots, the communal ties—was gone.

If you’ve ever been to Summit Rock, you’ve stood where much of this domestic work took place in the time of Seneca Village. The residents called this area “Nanny Goat Hill,” likely a reference to the livestock they raised here.

So on your next trip to Summit Rock, take a seat, take in the view, and consider: What would it have been like to build a home here as a Black New Yorker? How would it feel to lose this home? Where would you go next, and how would you rebuild? In 1857, Emancipation was 30 years old, and you were “free”—but what did that freedom really mean?

Jenny Schulte is the Senior Marketing Writer & Editor at the Central Park Conservancy.

TAKE A TOUR

Want to learn more? Join one of our expert guides on an official Seneca Village Tour. Explore this fascinating history as you walk through the landscape.